The Mental Mistake we Make with Retirement Spending

This orginal article was written by By Meir Statman for the Wall Street Journal.

The same mind-set that works so well when people are building their nest egg can damage their quality of life in retirement.

Imagine spending a lifetime acquiring habits that offer the promise of a longer, happier and more fulfilling life. Then imagine that to have that fulfilling life, you suddenly must abandon all those habits.

Not easy, is it? But that’s what happens when people go from work to retirement, from saving money to spending it. Too often, the same personality traits that facilitate saving for retirement become impediments when it is time to spend that money. The mental tricks we employ while working become mental mistakes when we move into the next phase of our lives.

The result isn’t merely a nuisance. It can lead to a much less satisfying retirement—one in which people spend too little money and spend it on the wrong things, as well as take on too much investment risk. It can greatly reduce the happiness of later life, a time when many people have the time and money (and wisdom) to enjoy their lives in a way they never could before.

Conscientiousness is a doubled-edged sword

This all sounds great. And it is—until it collides with retirement. Conscientiousness then threatens to keep people who have enough money to enjoy life from spending that money. As one man wrote in a blog about retirement saving and spending: “I bought in early to the idea of saving for retirement over consumption, perhaps without really thinking much about it. Along the way…I became frugal. Changing now would be traumatic for me.”

The lesson here is as difficult as it is obvious: We should beware of crossing the line from frugality to miserliness.

It’s all how you frame it

The mental tools of framing and accounting help us accumulate savings during our working years. We frame money into distinct mental accounts of “capital” and “income,” and follow the rule of “spend income but don’t dip into capital.” We set automatic transfers from our income mental accounts (wages and salary) to capital mental accounts (401(k)s and the like).

Yet these mental tools can backfire in retirement when it is time to spend. Think of a retired 65-year-old with a $1 million stock portfolio. He needs an annual $40,000 in addition to Social Security benefits to maintain his standard of living. Assume he earns $20,000 a year from a 2% dividend yield on his stocks, and $20,000 a year from a 2% increase in the value of his stocks. He can comfortably spend $40,000 a year during 30 years of life expectancy. But such spending requires crossing the boundary that separates income from capital mental accounts and dropping the rule against dipping into capital.

Many retirees can’t cross that boundary. So they spend much less than they can afford to, or they attempt to increase income, which means greater risk. They may buy high-yield bonds—which have a higher default rate—or stocks promising high dividends—which are concentrated in particular industries, especially banking and utilities, raising risk by decreasing diversification.

There are better ways to ensure prudent spending in retirement while allowing investors to maintain the psychological comfort of a wall between capital and income. One is by “managed payout” funds that pay a percentage of their value, such as an annual 4% “income,” in installments specified by investors. This “income,” in reality, is composed of a combination of dividends and capital.

Another method involves required minimum distributions, or RMDs. These government-mandated withdrawals from defined-contribution retirement accounts start at age 70½. The annual RMD rate at age 70½ is 3.65%, increasing to 5.35% at age 80, 8.77% at age 90, and 15.87% at age 100.

By absolving people of the responsibility for deciding when to cash in their savings, RMDs can serve as prescriptions for spending more than our mental barriers would otherwise allow.

The pain of regret

There’s another reason so many retirees find it difficult to draw on capital, however much they can afford to. It’s because spending capital—as opposed to income—increases the likelihood that they’ll suffer the searing pain of regret.

Compare John, who buys a laptop computer for $1,399 with dividends received today from shares of his stock, with Jane, who buys the same laptop today with $1,399 in proceeds from the sale of shares of the same stock. Now suppose that the share price rises 3% tomorrow. Jane is much more likely to suffer the pain of regret because she chose to sell her shares. For John the company’s decision as to when to pay dividends was out of his hands.

Of course, Jane would feel pride if the shares’ price fell by 3% tomorrow rather than rose, but the pain of regret that accompanies a 3% loss exceeds the joy of pride that accompanies a 3% gain.

To get around this emotional block, retirees should find alternative ways to tap their capital—ways that won’t burden them with the potential pain of bad choices. They could, for instance, set up a strict schedule of investment sales, such as at the end of each month, removing the responsibility for choosing the right times for sales. Or they can use the managed-payout funds mentioned earlier.

You’ll die sooner than you think

People don’t judge their lifespans very well—a miscalculation that can leave them once again underspending in retirement.

According to data from the Social Security Administration, a man reaching age 65 today can expect to live, on average, until age 84.3. A woman turning age 65 today can expect to live, on average, until age 86.6. About one out of every four 65-year-olds today will live past age 90, and one out of 10 will live past age 95.

A study of people’s beliefs reveals, however, that while young people underestimate their longevity, older people overestimate it. For instance, 68-year-old men have a 71% chance of living to 78 but believe, on average, that they have an 82% chance of reaching that age. Such overestimation means that people also overestimate how much money they will need in retirement—and underestimate how much they can spend.

I’m not suggesting people spend every penny they have by age 95. But most people have a lot more leeway to spend than they realize, and their misunderstanding of longevity only exacerbates their underspending.

Don’t leave the best for last

We have a tendency to put off spending for enjoyment, thinking both that it is financially prudent and that delaying will increase our gratification.

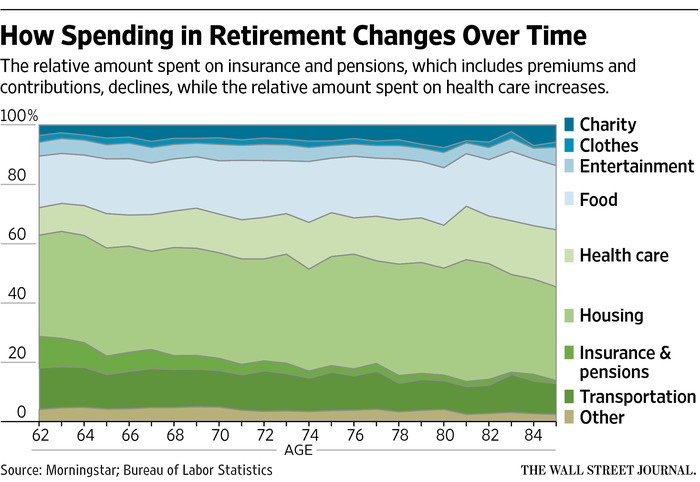

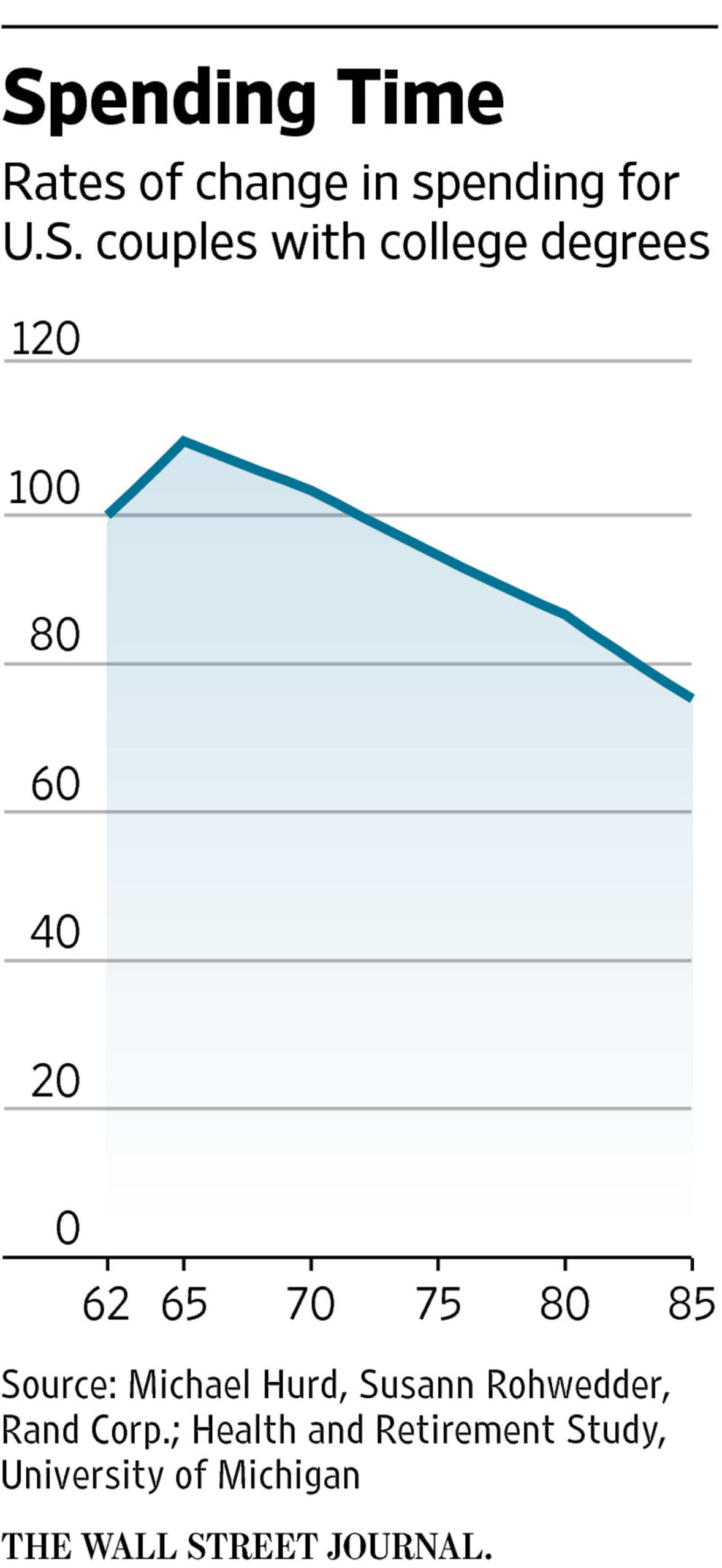

That is wrong in both cases. Take a cruise when you are 70 if you wish, but don’t delay it. Evidence indicates a pronounced tendency for diminished consumption beyond age 70, even among those with ample financial resources. A household headed by an 80-year-old spends 43% less than a household headed by a 50-year-old. Older people suffer physical limitations that make them less capable of spending money. And for personal reasons, such as the death of a spouse, they are less inclined to spend.

Spending isn’t just about the price

We often get advice from family and friends to spend more while we can. Spend at fancy restaurants, they say. Go on a cruise. But the better advice is to identify what can bring us joy, even if it departs from what brought us benefits in the past.

A couple I know never flew business class unless upgraded or paid with frequent-flier miles, because tickets cost as much as five times coach fare. That made sense when they were younger and trying to accumulate savings. But they hated traveling coach, especially as they got older. Eventually, they realized they could afford to fly business class for international trips. For them, that extra fare was worth much more than, say, going out 10 times for $100 meals at a pricey restaurant.

A couple I know never flew business class unless upgraded or paid with frequent-flier miles, because tickets cost as much as five times coach fare. That made sense when they were younger and trying to accumulate savings. But they hated traveling coach, especially as they got older. Eventually, they realized they could afford to fly business class for international trips. For them, that extra fare was worth much more than, say, going out 10 times for $100 meals at a pricey restaurant.In contrast, another couple recently bought a new car. They easily could have afforded a luxury car, but chose an ordinary one and donated the difference to a favorite charity. They saw the purchase of a luxury car as a kind of status-seeking they didn’t want. Instead, they derived expressive and emotional benefits from their donation.

Similarly, for many people during their work years, some spending is motivated by social status—“keeping up with the Joneses.” When we’re saving for retirement, such comparisons make sense, because it pushes us to strive to get ahead.

But that kind of comparison hangs on way too long into our retirement years. It only makes us spend too much, and on things that don’t give us true happiness. At this point, we shouldn’t be striving to make more, to achieve status. We should be striving to get the most joy out of what we already have accumulated.

It is better to give with a warm hand than with a cold one

Many people believe that the time to bequeath the majority of their estate is when they die. Part of it is out of fear of running out of money (often irrationally). Part of it is simply habit. But waiting deprives them of the joy of giving.

A father asked me for advice whether to forgive a substantial loan he and his wife made to their son for law-school tuition. He is at the beginning of his career and at the beginning of forming a family. They could easily forgive that loan without imposing hardship on themselves. It is money that would be going to their son in any event.

Why, I asked, would they insist on having him pay it back now, when he probably needs it the most, and they could enjoy the act of giving it the most?

Don’t try to beat the market

A lot of people look ahead to retirement and think: I’ll have so much free time, I’ll finally be able to manage my investment portfolio and not pay somebody to do it.

Resist that temptation. For one thing, trading by amateur investors is akin to baking by amateur bakers: You’ll never bake a good loaf, because you’ll be opening the oven door every few minutes.

What’s more, investors are notoriously bad at evaluating the risk they are taking with their portfolios. That’s because they are still thinking the way they did when they were in the workforce. They don’t realize that the wealth of young people is mostly in “human capital”—the income they are likely to earn during their working years. Younger people can take more risk with their retirement savings because human capital will cushion their fall.

The wealth of retired people, however, is mostly in retirement savings. They can’t afford much risk, because they have no human capital to fall back on. Placing part of their retirement savings into a well-diversified portfolio of broad-based mutual funds is prudent because such a portfolio isn’t likely to lose all its value. But placing all retirement savings into a venture, such as a retail store or new franchise, is less than prudent because all its value can be lost.

As an old commercial advised, you don’t have time to earn it anymore. Buy an occasional lottery ticket instead.