Why your credit card debt is about to get more expensive

This original article was written by Paul Davidon.

This article originally appeared on USA Today.

Credit-card users, home-equity borrowers and homeowners with adjustable-rate mortgages will likely see their monthly payments rise as the Federal Reserve’s interest rate hike Wednesday ripples across the economy.

All of those revolving loans have variable rates that go up or down based on the Fed’s benchmark short-term rate which it raised by a quarter percentage point.

“If you’ve got variable-rate debt, it could make sense to speed up those payments or refinance that debt to a fixed rate loan,” says Liz Weston, a certified financial planner based in the Los Angeles area.

For consumers with 30-year mortgages and other longer-term loans, the effect of the Fed’s move on their pocketbooks will be far more gradual. But the central bank’s plan, announced Wednesday, to gradually reduce the size of its $4.5 trillion balance sheet, is also likely to nudge up mortgage rates over time as the assets flood the market, lowering their prices and increasing their rates.

Car buyers may be affected, too, though they’re now benefiting from a highly competitive market for auto loans that’s keeping borrowing costs low.

“If you’ve got variable-rate debt, it could make sense to speed up those payments or refinance that debt to a fixed rate loan,” says Liz Weston, a certified financial planner based in the Los Angeles area.

For consumers with 30-year mortgages and other longer-term loans, the effect of the Fed’s move on their pocketbooks will be far more gradual. But the central bank’s plan, announced Wednesday, to gradually reduce the size of its $4.5 trillion balance sheet, is also likely to nudge up mortgage rates over time as the assets flood the market, lowering their prices and increasing their rates.

Car buyers may be affected, too, though they’re now benefiting from a highly competitive market for auto loans that’s keeping borrowing costs low.

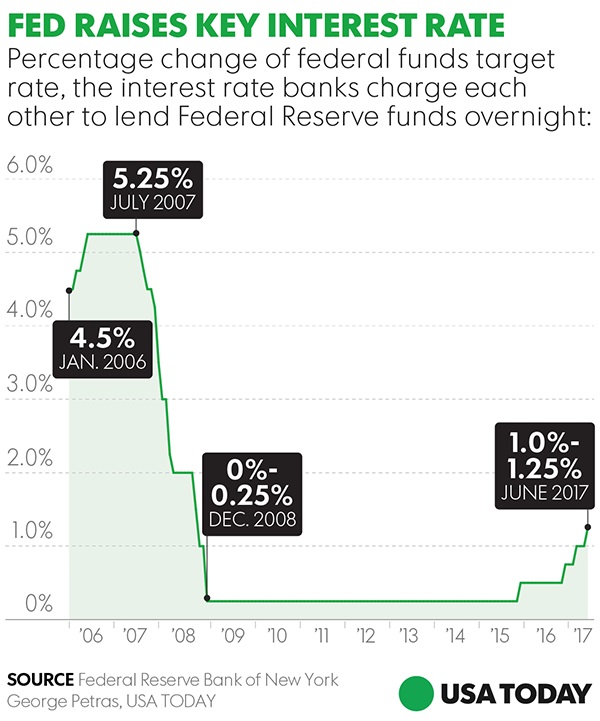

The Fed lifted its federal funds rate — which is what banks charge each other for overnight loans — by a quarter percentage point to a range of 1-to-1.25 percent following a similar March hike. A third quarter-point increase in 2017 is still expected later this year.

Here’s how the moves could affect consumers:

Credit cards, HELOCS, adjustable-rate mortgages

These loans will become more expensive since their rates are directly linked to the prime rate, which in turn is affected by the Fed’s key rate, says Steve Rick, chief economist of CUNA Mutual Group.

Average credit card rates are 15.07 percent, according to Bankrate.com. For a $5,000 credit card balance, a quarter-point hike is likely to add about $175 in total interest, says Bankrate Chief Economist Greg McBride. But with the Fed set to bump up rates three times a year through 2019, that could mean the addition of $525 in total interest annually.

Meanwhile, rates for home equity lines of credit are considerably lower at about 5%. A quarter point increase on a $30,000 credit line raises the minimum monthly payment by just $6 a month, McBride says. Three hikes this year would mean a $18 rise in the monthly tab. Borrowers could feel these effects within weeks.

By contrast, rates on adjustable-rate mortgages are modified annually. So the impact may be delayed but it could hurt. Three quarter-point hikes in 2017 likely would boost the monthly payment on a $200,000 mortgage by $84.

Fixed-rate mortgages

The Fed’s key short-term rate affects 30-year mortgages and other long-term rates only indirectly.

Thirty-year mortgage rates reached a 2017 high of 4.3 percent in March but since have retreated to 3.9%. Many factors have pushed down long-term rates, including still sluggish inflation prospects and global economic concerns that drive investments to U.S. Treasury bonds, which lowers their rates because they move in the opposite direction of rising prices.

Amid these forces, Fed rate hikes are a relative flyspeck, says Doug Duncan, chief economist of Fannie Mae. And, he says, Wednesday’s move is already baked into current mortgage rates.

“There shouldn’t be any dramatic spikes which cause buyers and refinances to abandon their home loan aspirations,” says Tim Manni, a mortgage analyst for NerdWallet.

All told, three rate increases in 2017 could increase mortgage rates by about a quarter percentage point, Duncan says, boosting the monthly payment on a $200,000 mortgage by about $30.

The Fed also announced on Wednesday that later this year it will begin to shrink the bond portfolio it amassed after the financial crisis to lower long-term rates.

Together, the rate hikes and the unwinding of the Fed’s portfolio could increase mortgage rates by half a percentage point a year, says Lynn Fisher, vice president of research and finance for the Mortgage Bankers Association. For that $200,000 mortgage borrower, it could mean shelling out an additional $180 a month by the end of 2019.

“I think for most people, buying a house isn’t contingent on interest rates … but (the prospect of higher rates) may help speed things up,” coaxing fence-sitters to pull the trigger sooner rather than later, Fisher says.

Auto loans

Three rate hikes this year theoretically would increase the monthly payment for a new $25,000 car by a total of $9.

But McBride says, “Competition among lenders is minimizing the increases on auto loan rates so don’t expect an across-the-board, quarter-point hike on car loans. There will be plenty of lenders that will hold rates steady or make only subtle changes.”

Auto loan rates average about 4.4 percent.

Bank savings rates

Since banks will be able to charge a bit more for loans, they’ll have a little more leeway to pay higher interest rates on customer deposits. Yet don’t expect a fast or an equivalent rise in your savings accounts or CD rates, many of which pay interest of 1 percent or less.

Low rates on loans have meant narrow profit margins for banks for years. They have a chance to benefit from a bigger margin between what they pay customers in interest and what they earn from loans.

Fed hikes totaling 0.75 percentage point the past 18 months have led to just a 0.15 percentage point increase in average CD rates and virtually no change in savings account rates, Rick says.